First American female Olympic champ never knew it

By Tom Emery

She broke barriers in an era when few noticed. And she went to her grave never knowing that she was an Olympic champion.

Margaret Abbott of Chicago was the first American woman to win an Olympic event, capturing first place in women’s golf at the second of the modern Games, in Paris in 1900. Incredibly, she thought she was competing in a local amateur event, and not in the Olympics.

The scenario may be attributed to the incompetence of the organizers, as the Paris Games were a resounding failure. In addition, the traditional medals for the top three Olympic finishers – gold, silver, and bronze – were not awarded until the next Games, in St. Louis in 1904.

Dr. Paula Welch, professor emerita in Health and Human Performance at the University of Florida, has extensively researched and written on Abbott’s life. She notes that many of the winners at Paris were presented with works of art, not medals.

“At the first modern Olympics, in Athens in 1896, a few medals were given,” said Welch, who has also extensively studied Olympic history. “But I’m not aware of any medals at Paris.”

Like many women golfers of her era, Abbott came from a privileged background. Born in Calcutta on June 15, 1878, she lived in Boston before moving to Chicago with her mother, Mary Perkins Ives Abbott, an accomplished author and essayist for the Chicago Tribune.

Mary Abbott rubbed elbows with the cream of Chicago society, including Charles Blair MacDonald, considered by some the father of amateur golf in the United States. MacDonald was the first President and designer of the Chicago Golf Club, the first 18-hole course in America, and introduced Mary and Margaret to the game.

“People who knew Margaret describe her as quiet, kind of shy,” commented Welch. “But she was very confident in her golf game. Peers called her a fierce competitor.”

In October 1899, the Abbotts journeyed to Paris, where Margaret was to study art under Edgar Degas and Auguste Rodin. The following year, the World Exposition captivated Paris, and the Olympics were relegated to a sideshow. Sprinkled throughout the long run of the Exposition, the Games opened on May 20 and closed on October 28.

The secondary status disheartened the Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the French founder of the modern Games, though he had been pushed out in a power coup with the government. The ignominious exit may have been a blessing in disguise for Abbott.

“de Coubertin was clear in his disapproval of female competitors,” remarked Welch. “Once he was gone, it opened the door for some women to compete. But the organizers hadn’t done anything like the Games before, and really didn’t know how, which caused some of the problems.”

Thanks largely to de Coubertin, no female athletes were permitted to compete in the 1896 Games at Athens. Of the 1,225 athletes at the 1900 version, only nineteen were women. Golf was one of the debut sports in Paris, and the competition was held at Compiegne Golf Club, thirty miles north of the city.

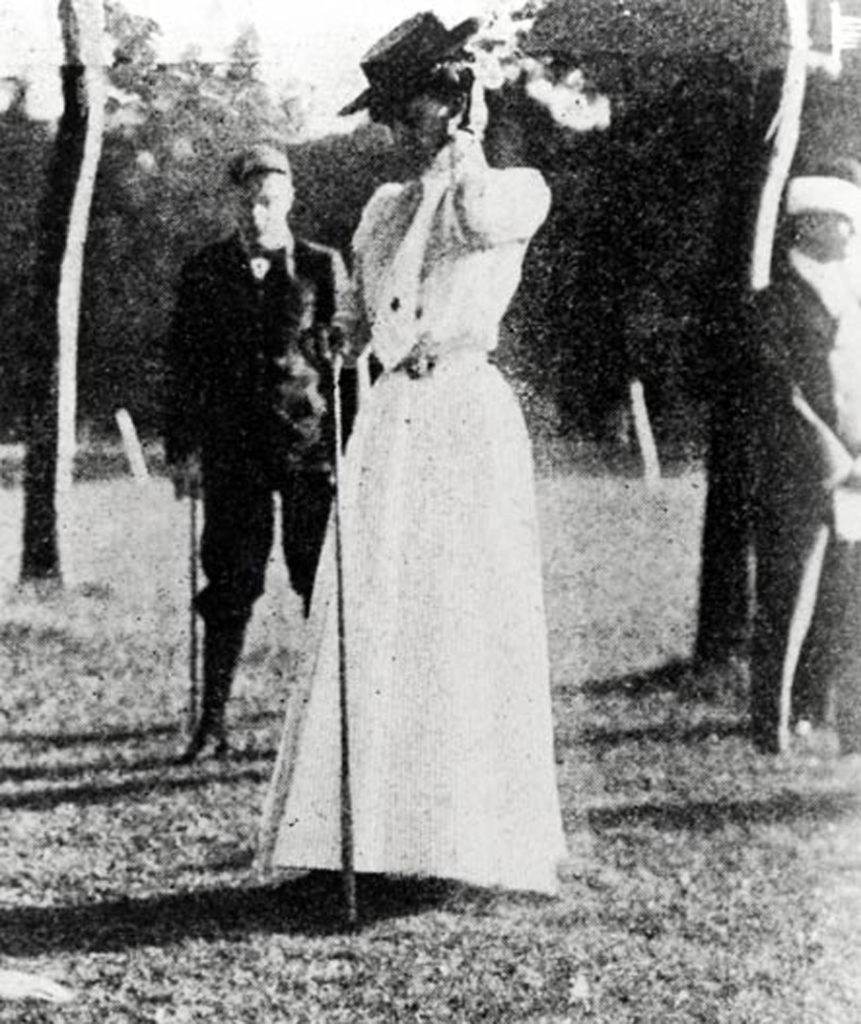

Ten women from two nations – the United States and France – showed up for the nine-hole tournament on October 3. Abbott’s future husband, Chicago satirist Finley Peter Dunne, later said that the other players “apparently misunderstood the nature of the game scheduled for the day and turned up to play in high heels and tight skirts.”

However, organizers did not bother to explain the event they were playing in. Believing the outing to be some sort of local amateur event, Abbott carded a nine-hole total of 47 to win by two strokes over fellow American Pauline Whittier, a descendant of poet John Greenleaf Whittier who was studying in Switzerland at the time.

In third place with a 53 was another American, Daria Huger Pratt, who was on vacation in France that fall. Soon after the Olympics, she divorced her husband and married a Serbian prince.

Tying for seventh, eighteen strokes off the pace, was Abbott’s mother, Mary. It the only time in Olympic history that a mother and daughter competed in the same event.

“Accounts in world newspapers indicate fairly good crowds saw that event,” said Welch. “Some of the spectators were in so close that the golfers had to alter their shots.”

For her victory, Margaret received a commemorative porcelain bowl, trimmed in gold. She also won the French championship around that time, but never was aware that she was an Olympic champion at any time in her life.

Two years later, she married Dunne. She died in Greenwich, Conn. five days short of her seventy-seventh birthday in 1955.

“In later years, she told family and friends that she thought the competition was more important than the French championship,” said Welch. “But she never knew she had won an Olympic event.”

Neither did her children. “I spent ten years – not every day, of course – tracking down her golf and Olympic involvement, and searching for her relatives,” said Welch. “This was in the days before the Internet.

“One of her sons, Phillip Dunne, was a screenwriter for Twentieth Century Fox,” continued Welch. “I asked him, ‘do you know what your mother did?’ and he was just amazed. He had no idea whatsoever.”

Golf returned once more to the Olympics in 1904, but only as a men’s event. The sport made a much ballyhooed-return to the Games in 2016 in Rio.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher from Carlinville, Ill. He may be reached at ilcivilwar@yahoo.com.